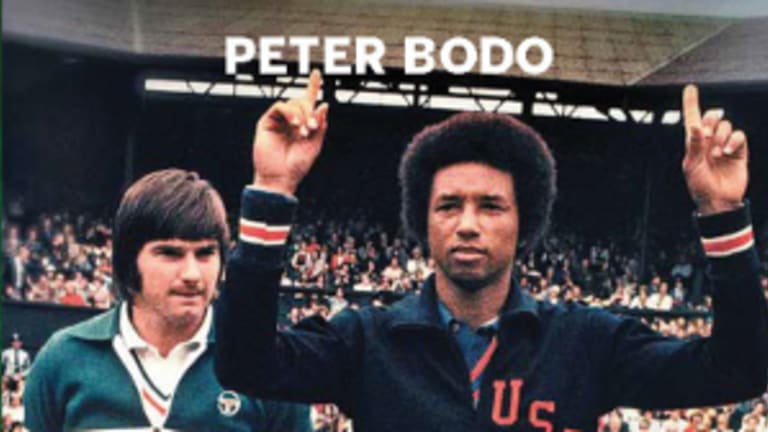

After an extended hiatus, the Book Club returns. Today my TENNIS.com colleague Peter Bodo and I discuss his new book about the epochal 1975 Wimbledon final, "Ashe vs. Connors," which can be purchased at Amazon.com.

Pete,

Forty years after one of the biggest upsets in tennis, a look bac

Published Jun 24, 2015

After an extended hiatus, the Book Club returns. Today my TENNIS.com colleague Peter Bodo and I discuss his new book about the epochal 1975 Wimbledon final, "Ashe vs. Connors," which can be purchased at Amazon.com.

Pete,

Book Club: Ashe vs. Connors

It's easy to see why the 1975 Wimbledon final between Arthur Ashe and Jimmy Connors deserves book-length treatment. It stands alone among Open era tennis matches. It was a battle that broke down along racial and generational lines, it was a stunning upset, and, in the dignified 32-year-old’s victory over the young ruffian, it provided one of the great feel-good stories in tennis history. The match wasn't the greatest ever, but it included a one-of-a-kind performance from Ashe.

I have a vague recollection of either following the match on TV (I was six years old in '75), or hearing the scores and understanding that the result was a shock—I may be retrospectively creating memories here, because as far as I know Wimbledon was only shown on tape delay in the U.S. in those days. But I wanted to start by asking you whether you were at Wimbledon that year, and also to talk a little about your personal relationships with Ashe and Connors.

And how did the match measure up when you looked back at it 40 years later? When I watch the YouTube clips, the most amazing thing to me is how fast they played—and Connors was famous for being slow! I know it's heresy, but it may even be a little too fast for my 21st century tastes.

Steve,

Contrary to what many readers might think, I was not born with a press credential dangling from my neck. I was not present at that historic final, as I was just embarking on the long road of my career and still fighting to get assigned to cover glamorous events like, oh, the U.S. Pro Indoor in Philadelphia in the middle of February, never mind Grand Slam events on foreign shores.

But being slightly older (clears throat) than you, I do have vivid memories of that match, and perhaps that helped motivate me to write this book. As a fellow mangler of words, you know how exploring something that remains somewhat unclear or unresolved in the imagination is far more tantalizing than the re-telling of an experience we know stone cold. I think you pretty much nail the importance of that match in your first paragraph, but of course we could not know just how resonant it would become at the time at happened. Who knew the degree to which each man would become a kind of larger version of that 1975 self in ways predictable as well as unexpected as the years and decades went on?

At the time of the match I had enjoyed very few interactions with either man, but over time I got to know both of them about as well as our respective roles in the sport allow. The thing to remember is that even though it was possible at the time for a journalist (at least a magazine or opinion journalist like myself) to cultivate authentic relationships with players in a way that is no longer feasible due to the growth of the game, even then, there was a kind of transaction at the heart of the interaction.

Ironically, it was less true with Ashe than Connors, but I believe that was a generational thing as well as a personal thing. Ashe, being a well-educated, curious, sophisticated man, had neither fear of nor narrow-minded contempt for journalists. It certainly helped that most of them appreciated him and his journey in tennis. For a long period Arthur was a playing editor for TENNIS Magazine. We sometimes drove up to Connecticut from New York for editorial meetings, and I enjoyed those trips because we talked about fishing and hunting, something we both enjoyed. Arthur often seemed remote, but he was never really cold—the word that most frequently comes to mind is "laconic," followed by "ironic." He was a very easy guy to be with, easy to share silence with.

Jimmy, for better or worse, was a different breed of cat, and everything in his background, from the role his mother played in his development to his vulgarity and "proud to be stupid" attitude, set him up as both a natural mark and scourge of journalists. For many years, though, I had an excellent relationship with Connors. I spoke on the phone at intervals with his mother Gloria, who in her simple way thought I was part of their "team" because I wrote positively about Connors's talents. I cut Connors slack where others of my ilk did not. I tried to see his point of view and represent it to the public. I had a soft spot for the rebel in him.

Ultimately, though, the relationship went south when he somehow became convinced—erroneously—that I wrote something slanderous about him. Jimmy being Jimmy, he was not going to change his mind and I certainly wasn't going to bend over backwards to change it. So we no longer speak. It was never that easy to speak with him anyway, because the thing with Jimmy is that he was a very uptight guy; you could sense his insecurity, like he was never sure what to say if the conversation strayed away from him and his tennis. It was work to have a conversation with him. It was just another of the ways in which he was the opposite of Arthur, who for all his good manners and education could have a conversation with anyone, and on anyone's level.

My experience of these two men was one of the reasons I wanted to write this book. I just felt like I had a good grasp of their personalities and issues, I knew where the bodies were buried, I saw where their careers arced. I thought it would be interesting to just take their two lives more or less from day one and weave them together and end it with this spectacular upset, which to me was a very fitting commentary on who each man was, and what each man represented. And it may seem like Connors got the short end of the stick, but if you look at how life turned out for both of them, that's a pretty myopic view. Connors got more than his share of the glory, and we won't even get into the issue of mortality.

I know what you mean about how fast they played; it's funny when you compare it to today's players, isn't it? But I'll tell you this, watching that match once again reminded me of the gap between live tennis and canned, broadcast, or streamed tennis. Ashe had an economy of motion that you had to witness to truly appreciate. There was a kind of grandeur to his game, at least when he was making his shots. He was explosive, but not in that burly, Stan Wawrinka way. And Connors, well, he was the most mobile player i've ever seen. I'm not sure he ever did get out of his crouch. You don't hear it said often, but I really think Jimmy was about as different from your "typical" tennis player as you can get. I really can’t think of anyone who's anything like him. When I try, I come up with the names of guys who never accomplished anything close to what Jimmy did.

Pete,

I've always thought Ashe vs. Connors made for a perfect Levels of the Game-type treatment, where a writer uses a match as a forum for talking about the competitors' lives and what they represented. It also makes sense, of course, because Levels of the Game itself was about another Ashe match, against Clark Graebner at the 1968 U.S. Open. As you wrote in your book, in the tennis world, Ashe was automatically a figure of interest and contrast throughout his life.

We get a full picture of both men here, and your conversations with Ashe's friend Charlie Pasarell adds a lot to his story. I also liked that you were able to complicate the way we see each player a little. Most of us know all about Jimbo's status as a self-proclaimed outsider, and Ashe's pioneering wins on court and humanitarian efforts off it, so it made sense to show a slightly different side of each of them.

Here we see Ashe caught in between worlds, "too black" when he's young, and then criticized as "too white" when he's older. Sometimes the victim of racism, other times "the beneficiary of touching acts of support."

And here we see Jimbo as perhaps not quite so far "outside" the tennis world as he and his mother wanted us to believe. I had never thought of it before, but it's true that Gloria Connors and her mother, Bertha, had been deeply enmeshed in amateur tennis for decades—it was their lives. Maybe we can see now that Gloria's "us vs. them" worldview was partly a strategy, one that worked to perfection with her son.

It's also interesting how small the world of tennis was at the time, small enough that it could unite these two men who had such different beginnings. Ashe and Connors followed strikingly similar paths, and their lives overlapped in surprising ways. Connors was born near St. Louis; Ashe moved to that city and practiced on the same indoor courts as Jimmy would. Each gravitated to Los Angeles, Ashe at the start of the 60s and Connors at the end of that decade. Each was mentored by the two Panchos, Gonzalez and Segura, and each won the NCAA singles title while playing for UCLA. Their differences were almost as much generational—Ashe was from the buttoned-down "Mad Men" era; Jimbo from the freewheeling late-'60s—as they were racial. I was struck as I read the book about the power of a sport to bring two people closer together than their nation could.

Steve,

That's an astute point you make at the end there, about the power of sport bringing Ashe and Connors closer together than "their nation" had. Sport provides engagement; it's a natural byproduct of what sports are. We're lucky that way. Yes, Ashe is the king of the Levels genre for sure, and one of the things I enjoyed about doing this project was that so much of the research was pre-existent. I could just really sift and weigh and pick the bits I wanted to use in my main mission, which as you surmised was not only to shine a light on the contrasts between the men (which seem somewhat obvious) but also on the similarities.

Ashe and Connors were very different men, but in the dominant area of their lives, one which shaped much of what they did and thought, they were similar—they were tennis players. Both liked the Playboy club (some Ashe fans might be mortified). Both were catered to, almost everywhere they went; that will have a somewhat ruinous effect on anyone, including a wonderful and decent man like Ashe. They also traveled in the same circles, toted the same man purses, shopped in the same expensive boutiques, looked upon women in a similar way even if their needs and desires were somewhat different—as people who had specific, limited roles to play.

One of my "favorite" glimpses into the less-than-entirely-noble side of Ashe is that little anecdote first conveyed in his book, Portrait in Motion, about his break-up with a steady girlfriend who had traveled extensively with him during the year he wrote the diary. I believe they were up in Birmingham when Arthur got up one morning and more or less said to this Canadian lady, "That's it, it's over" and took her to the train station. That's pretty cold. They seemed pretty close, he wrote quite a bit about her, and I believe at one point he even met her parents. Perhaps there was a lot more to their bust up, and he was just trying to be discreet. I don't think so, though. He could have made it clear if that was the case. I think he just decided to dump her, offered not much explanation, and found himself footloose and fancy free again an hour or two later. Maybe it's better that way, but it struck me as kind of strange. Then again, Ashe was a good communicator of ideas, perhaps less so of feelings.

Conversely, for all the heat Connors took about his mother, there was something touching and more than a little sad about his devotion to her. It was absolute, like something out of a Tennessee Williams play. Can you imagine talking to your mother on a daily basis? Four, five times on some days? That’s something.

One of the things I wanted to stress was what a small world all these folks inhabited, which you picked up on and I think really comes through in the account of Gloria's early years, and then in that seam period where Jimmy is with Segura in Los Angeles, and Arthur is just about to graduate from UCLA. That whole camp thing they were doing up in Pasadena, with Stan Smith, Ralston, Billie Jean, Pasarell, Osborne, van Dillen, Lutz—what times they must have been for a player!

Pancho Segura liked both Connors and Ashe, and were he not coaching Connors he would gladly have told Ashe how to beat him. After all, as much as he ingratiated himself with the Hollywood set, Segura always remembered that he was one of the "brown people." But all of these guys had an attitude and a set of values that transcended race, creed and religion. They had a code, a "survival of the fittest" ethic. If you couldn't beat a guy, you shut up. You didn't whine that your ex-coach helped the guy, or your buddy told him your forehand broke down under pressure and therefore he beat you. They were all in it for the action. Kind of like gamblers. You got your butt kicked by some kid and they all laughed at you instead of running the kid out of town. There were big dogs and little dogs and all different kinds of dogs in between. Nobody got anything he didn't earn. It was a great period for American tennis.

Pete,

When I watch clips of Ashe and Connors at Wimbledon, sometimes I find myself thinking, "I wonder what the British crowd thought of watching two Americans play in their final." We don't see many, or any, all-American Grand Slam finals anymore, but it was a fairly common occurrence over the last quarter of the 20th century. If nothing else, Ashe and Connors showed the world the variety of personality types that this country can produce.

Speaking of the U.S. game, I'm glad you mentioned—and unearthed in your book—that fertile, and fairly unknown, period of time for tennis in late-’60s Los Angeles. We've probably both read our share about the L.A. Tennis Club of the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s, and how Perry Jones helped develop Jack Kramer, Bobby Riggs, and Pancho Gonzalez there. But I didn't know much about the next-generation, "Mod Squad" version of that scene, when Gonzalez and Segura were the teachers, and Ashe, Smith, Pasarell, Ralston, Lutz, Billie Jean, and then Jimbo were the students learning from them and from each other.

I wonder, as the U.S. continues its long search for its next champion, if there's anything to be learned from how the sport was passed down and passed around then. The L.A. scene wasn't a tennis factory, exactly, though the players all competed with each other. With Gonzalez and Segura involved, it reminds me a little of what we're seeing among the top players today. They've found that they have a lot to learn from the experience and tactical wisdom of former champions like Lendl, Edberg, Becker, Ivanisevic, Chang, Davenport, and Mauresmo. I had never heard the story of how Gonzalez soft-balled Connors to death in the early 70s, and how Pasarell passed that information on to Ashe at Wimbledon.

You write one book, dig things up from the past, and more possible books and stories emerge. Thanks for writing this one, Pete.

Steve,

Interesting that you mention that this was an all-American final. The funny thing is that it was the first such final at Wimbledon since 1947, when Jack Kramer beat Tom P. Brown, the son of an ink-stained wretch like us, in the final. Crazy, huh? So we've had some rough times as a tennis nation before, at least at certain tournaments, like Wimbledon and Roland Garros.

As for the personality types, Pete Sampras vs. Andre Agassi may have come close to rivaling the contrast between Ashe and Connors at a very basic level (introvert vs. extrovert, conservative vs. flamboyant). But they didn't measure up to the same degree at the level having to do with what I would call the internal life of either man. Have two men ever been as different, intellectually and emotionally, as "Artie" and “Jimbo”?

I think Southern California became such a hotbed because the game was already trembling at the brink of explosion into the Open era—note that while Ashe, Connors, Smith, Ralston, Lutz et al were “Open” players, they were basically on track to be stars well before the game went Open in 1968. But it wasn't quite there, yet, so there as nowhere else to go. Being Americans, these players were hungry for competition, and willing to uproot. Members of a relatively wealthy, mobile society, they sought out each other, and the best coaching. Thus, the game in the U.S. became extremely centralized and it reached critical mass.

If you wanted to become a great player back then, you had two not entirely unrelated courses: You could head west (which became more appealing as more players embraced the choice), or attend a university with a great tennis program (preferably in the west). The college option may be the only thing that actually kept some players down in Texas at Trinity, or in Florida, or back East. Were Ashe a young man in Richmond today, he might have elected to go down to Bollettieri’s academy in Florida, or to board at the Tennis Champions Center in College Park, Md. Perhaps he would be putting in time at Harvard while getting high-quality boutique coaching from the USTA or some other interested, powerful party. There was life elsewhere on planet tennis in the late 1960s, albeit not a hell of a lot of it.

People sometimes ask me whatever happened to Southern California tennis. I don't think anything happened, at least not anything negative. One of the major changes wrought by Open tennis was the swift decentralization of the game, accompanied over time by the rapid growth of the game in Europe, South America, and Asia.

Those days you mention were really the last great days of amateur tennis. it may not stand out in the book, but this image of Ashe and Pasarell driving up to Pasadena early on Saturday mornings to help teach in those clinics always brings a smile to my face. They got paid, Charlie said, just about enough to buy a sandwich for lunch and maybe go to a movie in the afternoon. Yet they already were two of the best young players in the world, destined to be champions and men of great influence in and out of tennis. That kind of innocence is long gone, of course. Much has been gained; much also has been lost.

You can purchase Ashe vs. Connors at Amazon.com.